The term “Wasteocene”, or “waste age” entered the international cultural debate about five years ago, at the beginning of April 2017. It made its debut thanks to an article of about thirteen pages, supplemented by about fifty bibliographic references that have been published. by South Atlantic Quarterly It was signed by Marco Armero (CNR Institute of Mediterranean Studies) and Massimo de Angelis (University of East London). It is possible that this journal published by Duke University Press, though more than a hundred years old (1902), is not known to all, especially in Italy. visit then this sitewhich illustrates her line. It was founded by American historian John Spencer Bassett (1867-1928) at Trinity College (now Duke University) with the aim of promoting “freedom of thought”. Bassett was a very controversial figure, as described World Health Organization.

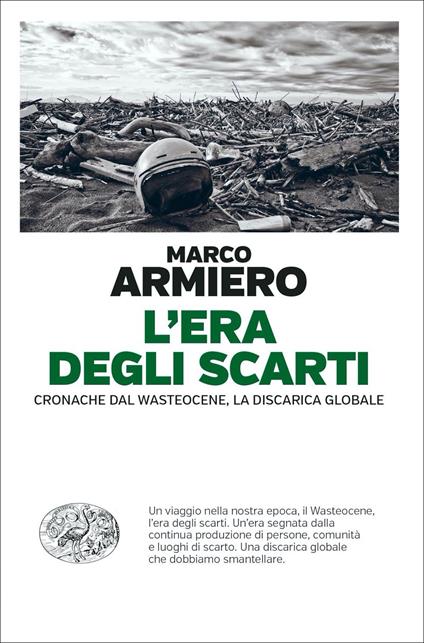

Back to the article by Armiero and De Angelis, from which Marco Armero’s book L’era degli scti. Records from the Wasteocene, a world landfill ”(Einaudi, 2021), it can be said that they foresaw its main themes. It was called The Anthropocene: Victims, Storytellers, and Revolutionaries And even then, he hinted at who was the subject of the authors’ criticism. By exposing some emblematic cases of resistance to environmental injustice, such as that of Orissa (Eastern India), Pukaliba (Uganda), Aboriginal Australians and especially the “Land of Fires” (Campania), the authors set out to demystify the traditional narrative that the Anthropocene refers to in capitalism as the driving force to the socio-environmental crisis. In essence, they transferred responsibility from the human race, which is an inconspicuous whole with the same flaws, to an economic system and its decadence.

After all, the criticism of the Anthropocene and the replacement of the term by Capitalocene is now long-standing (2014) and goes back to Jason W. Moore, as the author translated into Italian with “Anthropocene or Capitalocene” (Ombre corte, 2017). Capitalism, according to this current of thought, is a system based on the subordination of nature, human and non-human, to the needs of production and the accumulation of wealth. In the article already, Armiero and De Angelis went beyond the term Capitalocene as he rejected it as Wasteocene, to emphasize the polluting nature of capitalism and its persistence in the biological social fabric, as well as reveal the accumulation of side effects, both within human bodies and from those of planet Earth.

Basically, according to them, the Wasteocene would be a feature of capitalism and better suited to demystifying traditional Anthropocene accounts.

The book signed by Armiero develops, expands and consolidates in four dense chapters enriched by a broad bibliography, the concepts anticipated in the article, and validates the Wasteocene theory with extensive and detailed case studies which, in Chapter Two, “also deals with Italian issues, such as the Fagnot case.” At the beginning of this chapter , Armero reminds us that the main role of historians is not merely to remember the past but also to organize collective memory so as not to forget.The other chapters deal with the order of the passage from the Anthropocene to the Pseudocene, the latter ‘under the microscope’, and finally its subversion.

It was useful to read this book during the holidays and see the garbage cans full of all kinds of waste, also abandoned on the floor and a clear picture of our physical waste. But be careful, the waste, or rather the scraps, that the book talks about are not only those in rubbish bins or landfills, but also the human beings whom the system puts on the margins of society, the vulnerable communities that endure the inconveniences that the users of the social-environmental welfare dumps avoid. “.

The idea that the poor are poor because they are unable to recover from their circumstances on their own is false and the book convinces us that inequality, unfortunately, operates in the system. Moreover, even the most socially sensitive pronouns make it clear, following the teaching of Francis who constantly speaks to us about human “waste”. For example, in a recent interview with the Archbishop of Milan, Mario Delbini (Corriere della Sera, 12/31/2021 regarding labor market grievances and the phenomenon weak work, is reading: I’m also a little ashamed. We haven’t done everything we can do. We were not aware of what price it was for our well-being. Taking into account, among other things, the waste crisis of the 1990s and 2000s in Naples, Armiero’s book stigmatizes the toxic narrative that considers the victims of degradation to be the culprits, while naturalizing the “socio-environmental relationships that produce people and waste places”.

Toxic narratives blame individuals for being poor, dependent, or sick. as it happened during full closure Because of the epidemic, with the strict rule of staying at home, without thinking about the consequences for those who did not have a large, clean and comfortable home. The book asks questions that can embarrass those who are not accustomed to questioning themselves, they do so accurately and without deductions for the reader. Referring to the story of an activist from the Pianora (NA) landfill, she gives us an instruction manual for the Wasteocene which contains, among other things, the following rule: “Don’t ask yourself where the unwanted remains are for your ultimate well-being.” How many times have we done this or was it enough for us to find clean streets and sidewalks without worrying about who lives near the dumps and who is rebelling?

After all, isn’t the normalization of unjust social and economic relations to justify the violence of repression a feature of the Wasteocene? Armiero concludes by saying that for the process of true emancipation, control over the means of production is not enough, “if we do not transform Mutual Socio-environmental relationships of places and people.” For more on this, see World Health Organization. The issue is complex and the difficulties to be overcome are many but in the meantime, between one streak and another, it is good to ask what can be done to not cooperate in the slow and hidden violence of the prevailing order and not succumb to violence. The indifference virus.

“Infuriatingly humble social media buff. Twitter advocate. Writer. Internet nerd.”