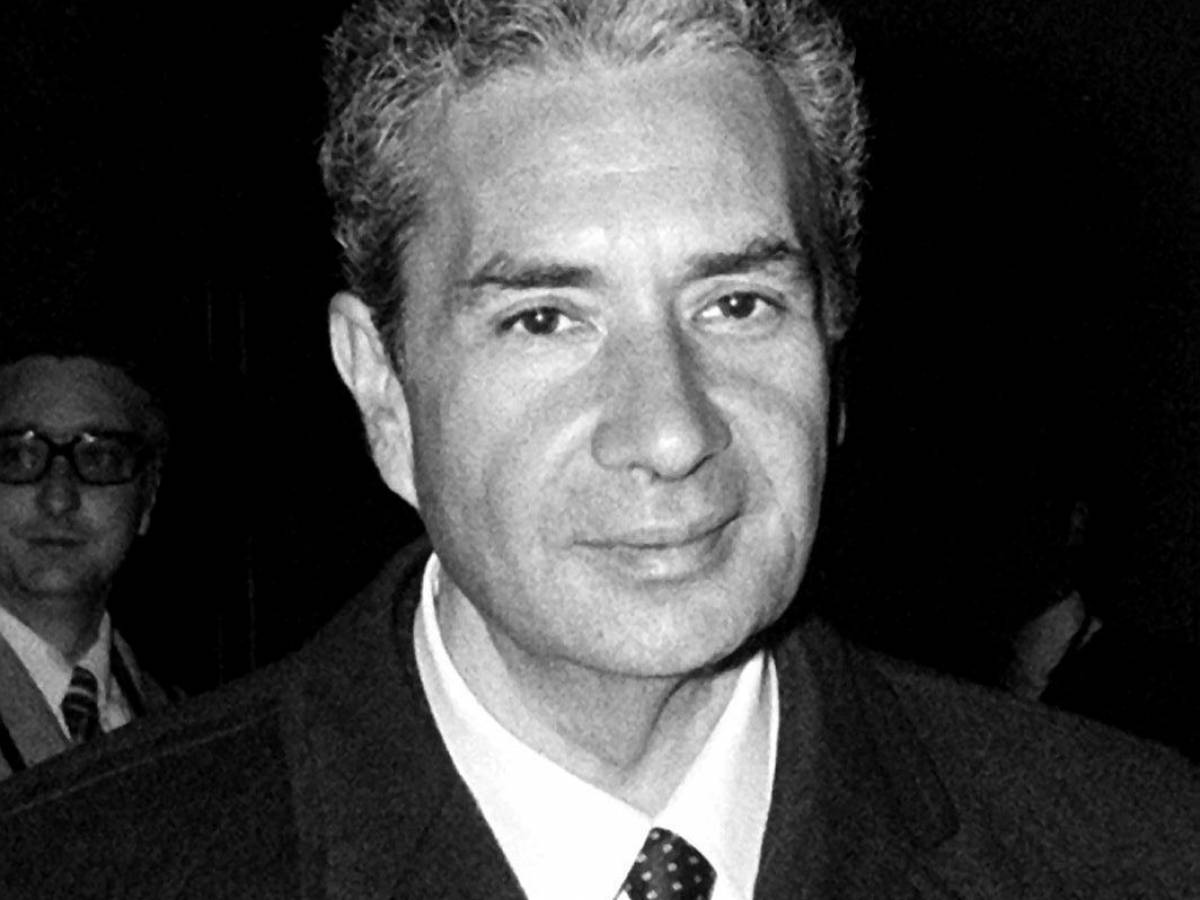

“The history of the Italian Republic is intertwined with many legends. One of these is Ludo Moro.” This is the beginning of the book El Ludo Moro: Terror and the Cause of the State 1969-1986, published by Laterza and signed by university professor and researcher Valentine Lomellini. A fitting start certainly, if you think about the aura of mystery that has long hovered over one of the most controversial topics by anyone dealing – business or sentiment – with contemporary history. Under-the-table agreement by the secret services on the mandate of Aldo Moro to stop the Arab-Palestinian terrorism rampant in Italy; Pact with Satan. A legend, indeed. Indeed, the interpretation of the so-called Lodo Moro – with its existence being considered correct – varies greatly depending on the views, which can from time to time be conditioned by personal opinions, studies conducted, political leanings and the more you have, the more you put. With this book, Professor Lumilini attempts a very brave act in an age of public information, especially for those who want information to bend to their emergency needs: she tries (and succeeds) to explain what happened to Ludo Moro. According to his personal opinion, but the papers are on hand, after working six years and consulting about 30 thousand pages of documents found in more than twenty archives between Italy and Europe. The result is a rigorous historical work, a clear cross-section of strategic years of tension, massacres and political terror. The years in which Italy somehow escaped Middle Eastern terrorism, with the exception of some bloody attacks that left about sixty dead on the ground (Fiumicino, December 17, 1973; Synagogue of Rome, October 9, 1982; Fiumicino, December 27, 1985; Achille Lauro, 8-10 Oct 1985; Fiumicino, December 27, 1985). A book, this, which also illustrates – and perhaps above all – the origin of a name that is misleading in some respects. By reading these pages we actually discover how “Ludo Moro” is actually attributed not only to the police statesman who was murdered on May 9, 1978, but to a large number of people. On the occasion of its release in bookstores we interviewed the author.

Professor Lumelini, how was this book born?

This is a good question. Actually I was born by chance. For years I have worked on a comparative reconstruction of the policies of Italy, France, Great Britain and Germany in relation to Arab-Palestinian terrorism since then Monaco massacrein the Lockerbie massacre. By carrying out this study, I was able to view a series of documents that instructed me to re-evaluate, or rather, rethink the question of the award and the alleged exceptions to the Italian “status”. From here, and especially from a document dated October 23, 1973 concerning negotiations between Italy and the Palestine Liberation Organization in relation to some terrorists imprisoned in our country at that time, I began to question myself about this and to ask why Ludo Moro was called. In this way, while in fact all documents – both in Italian archives and abroad – indicate that the ludo was not a “Ludo Moro”, but the result of diplomatic work done by different people.

In the course of these searches, did you find something you weren’t expecting?

There are many new features in this book. The award is usually given as a kind of silent agreement; It has also been called the “Intelligence Award”. Indeed, with this work, in the meantime, the actual existence of the award and secondly the fact that it was not a deviation from state politics, but a real state policy, was reconstructed. He showed that his fatherhood is not Aldo Moro, but choral—Mariano Romor, Giulio Andreotti, Bettino Craxi take part in these events, to name a few—and showed that the interlocutors are not those whose history they were contemplated. There has always been talk of a close agreement between Italy and the Palestinian resistance, but in fact the agreement between Italy, the Palestinian resistance, but – especially from 1973 onwards – with a series of “sponsors” of international terrorism: Libya, Iraq and Syria.

Why, then, is this agreement ascribed to Aldo Moro alone?

The convention is referred to as “Ludo Moreau” in a series of passages. The definition developed between the eighties and the nineties, when the general idea began to emerge that there was an agreement between Italy and the Palestinian resistance in general. This is especially after a series of articles published weekly panorama. However, the moment when the expression giving the title of the book was born was in the mid-2000s, when the Honorary President of the Republic, Francesco Cossiga, was first in a letter to Vincenzo Fragala, a member of the massacre commission and his deputy. From An, then in an interview with Aldo Cazzullo on Corriere della Sera In 2008, he spoke of and talked about “Ludo Moreau” to explain what he believed to be the true causes of the Bologna massacre.

So this is basically a misunderstanding?

Like many others when addressing this topic. Just to give an example: the prize has never been embodied in the failure to arrest guerrillas on Italian soil, and there is no kind of “prohibition” of arresting terrorists or their impunity. Rebels are always arrested and then, thanks to the intervention of the Interior and Foreign Affairs and the cooperation of some judges, and even – in 1976 – the then President of the Republic, Giovanni Leon, who pardoned some Libyan terrorists, they were liberated. So the award takes the form of a facilitation process, but never in the prevention of arrest. It is a policy that has been developed at a very high level and it is a thesis of this volume that there is a large exploitation of Moro’s character. In the book, a document is cited from the fall of 1971 in which an internal body of the Ministry of the Interior headed by Franco Restivo claims, in the gossip government, that Moro is financing Al-Fatah. This is an indication of the strong exploitation that occurred in reading Aldo Moro’s openness to Mediterranean politics and the Israeli-Palestinian issue. And if we consider that at that time Moro was Secretary of State, we realize how dangerous and troubling the spread of certain information that was believed to be reliable.

Do you expect criticism?

I like dealing with complex issues that aim to be able to think about complex issues from our national history. So yes, I expect criticism from both sides. But it means I did my job well.

“Freelance social media evangelist. Organizer. Certified student. Music maven.”