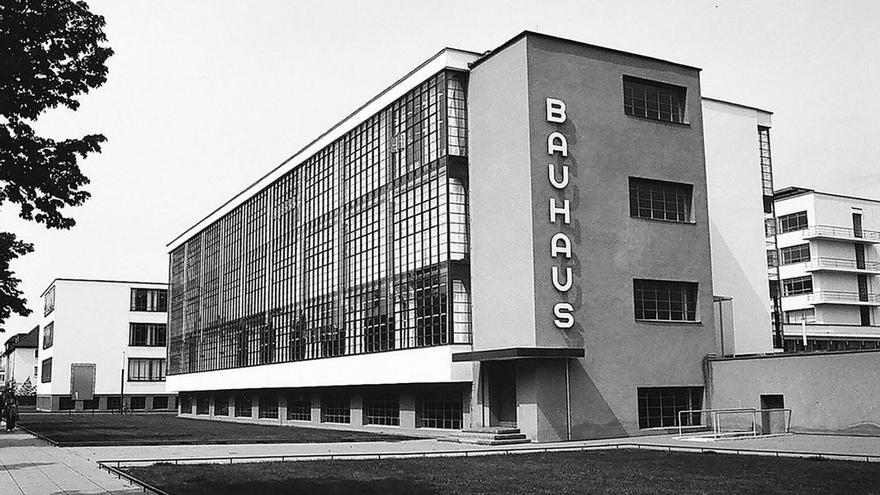

The Bauhaus, the German artistic and architectural movement so identified with the avant-garde and modernism that Adolf Hitler forced him into exile or deportation, also had “collaborators” and even ardent associates of the Nazis. The exhibition, which opened yesterday in Weimar, the school’s birthplace, reveals the links of some of the students who chose to remain in the Third Reich, while teachers such as Josef Albers, Walter Gropius, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe emigrated to the United States. States.

“The path to be followed after the school was dismantled, in 1933, was not the same for everyone. The lives of those who went into exile are well documented. And so are the lives of those who were deported and died in Auschwitz. But over the years, “little was known About those who collaborated or worked on the design of the so-called concentration camp bathtubs, which are in fact crematoria,” Professor Anke Blom, curator of the Bauhaus and National Socialism exhibition, explains to EL PERIÓDICO.

It is actually three shows – The Political Battle over the Bauhaus, 1919-1933, Outlaws, Confiscated and Modified, 1930-1937 and Vital Presence in Dictatorship, 1933-1945 – spread across three buildings, the New Museum, the Bauhaus Museum and the Schiller Museum. “There’s not enough space in Weimar to hold a lot of material, so we decided to divide it into three,” says Bloom. In all, they collect 450 objects, many of which are on loan from museums in both Europe and the United States, consistent with a school that revolutionized architecture, design and the visual arts.

Through virtual reality, the legendary exhibition about the school that opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1938 is recreated, but it also reflects what has been overlooked until now, such as the collaboration of its students with the Nazis.

Survival

“The best way to get an idea of the scale of what happened is in statistics. Of the 1,400 students the school had, until it was dismantled by the Nazis, 900 of them went to Germany. Of these, 188 joined the Nazi Party, the NSDAP, as militants,” he continues. Commissioner. Some may do this in order to survive or believe that adapting is the only way to avoid professional disqualification. “No one was forced to join the party,” warns Blum, who recalls that there were people, such as the sculptor Heinrich Bassedov, who had already joined as militants in 1930. “There are many different circumstances in this group of 900 people that followed.” In the country,” the commissioner admits. There will be those who did not immigrate because their families or their economic situation did not allow them to do so or because they did not have the necessary contacts in the United States or in other parts of the world.

But there were also Hitler’s “ardent fanatics” and the mass movement he drove to mass delirium. So were students like Austrian Fritz Ertl, who designed fake bathtubs at Auschwitz, the extermination camp where some of his former colleagues died. “It was a very heterogeneous group,” emphasizes Blom, a researcher at the Weimar Classic Foundation, who co-curates the exhibition with Professor Elisabeth Otto, from the University of Buffalo (USA), and Professor Patrick Rösler, from the University. Erfurt (Germany).

His work begins from preliminary studies in 2009, during the 90th anniversary of the Bauhaus, and expands in 2019, with its 100th anniversary. Seminars were held in Weimar that focused on links with National Socialism. The current exhibition is the first to offer the possibility of “understanding this other perspective, less flattering and more critical,” as Bloom puts it. This means that it is outside the academic sphere and open to the average visitor.

The Weimar elections are not causal. Not just because it is the city where the interwar republic of that name was founded, from 1919 to 1933, or where Walter Gropius founded his Bauhaus school. The Classic Weimar Foundation undertakes an extensive mission to critically examine the past of the city, which, as Blum recalls, “astonished Hitler,” a regular guest at the legendary Elephant Hotel.

The current situation worries Blom, a resident of Weimar. The city belongs to the state of Thuringia, where the far-right Alternative for Germany party could become the leading force in the regional elections next September. Its leader is Björn Höcke, head of its most extremist wing, who is on trial for using Nazi slogans in public. “It is terrifying,” the professor sums up, the willingness of a large number of voters to vote for this party, in a city and a country where Nazism is still present.

The opening will be followed by opening to the public, today, which is the day on which Germany commemorates the surrender of the Third Reich or Liberation Day from Nazism. Also on this day, a new museum opened about the 20 million forced laborers the Nazis owned.

“Freelance social media evangelist. Organizer. Certified student. Music maven.”